Almine Rech, Shanghai

August 25 - October 14, 2023

August 25 - October 14, 2023

"I am a poet” and "I am a Buddhist” are the two ways John Giorno most often introduces himself. These two identities are central to our understanding of the artist. However, as a Zen monk once said, "How can we appreciate the beauty of the moon when we are in it?" It would be futile to look directly for traces of Buddhism in Giorno's artworks. We shall take a detour to appreciate his art.

From the 1950s onwards, North America began to receive influence from Buddhist preachers led by D.T. Suzuki, Chögyam Trungpa, among others. Some of the most prominent artists, poets, and scholars of the era, including Giorno, integrated Buddhism into their vision in one way or another. However, besides Giorno, very few lived their entire lives in a way almost as 'Upāsaka' — the follower of the Buddha. The artist's bond with Buddhism began to germinate during his undergraduate years at Columbia University, and he did not limit his interest in this religion to an inner conversation or spiritual solace within himself.

In 1975, Giorno visited India for the fifth time. It was during this trip that he managed to invite his guru, Dudjom Rinpoche, to visit the United States. Giorno raised funds to help Rinpoche establish the Yeshe Dorje temple in Greenwich Village, New York City, which was eventually founded in 1976. Giorno devoted all his energy and time to this temple in the first few years. As he recalled this moment of history, he said: "I had accomplished everything I wanted to do.” In 1982, Giorno transformed his house into a Tantric meditation hall, and used it to hold a grand and solemn Fire Puja every New Year's Day for more than 30 years before his death.

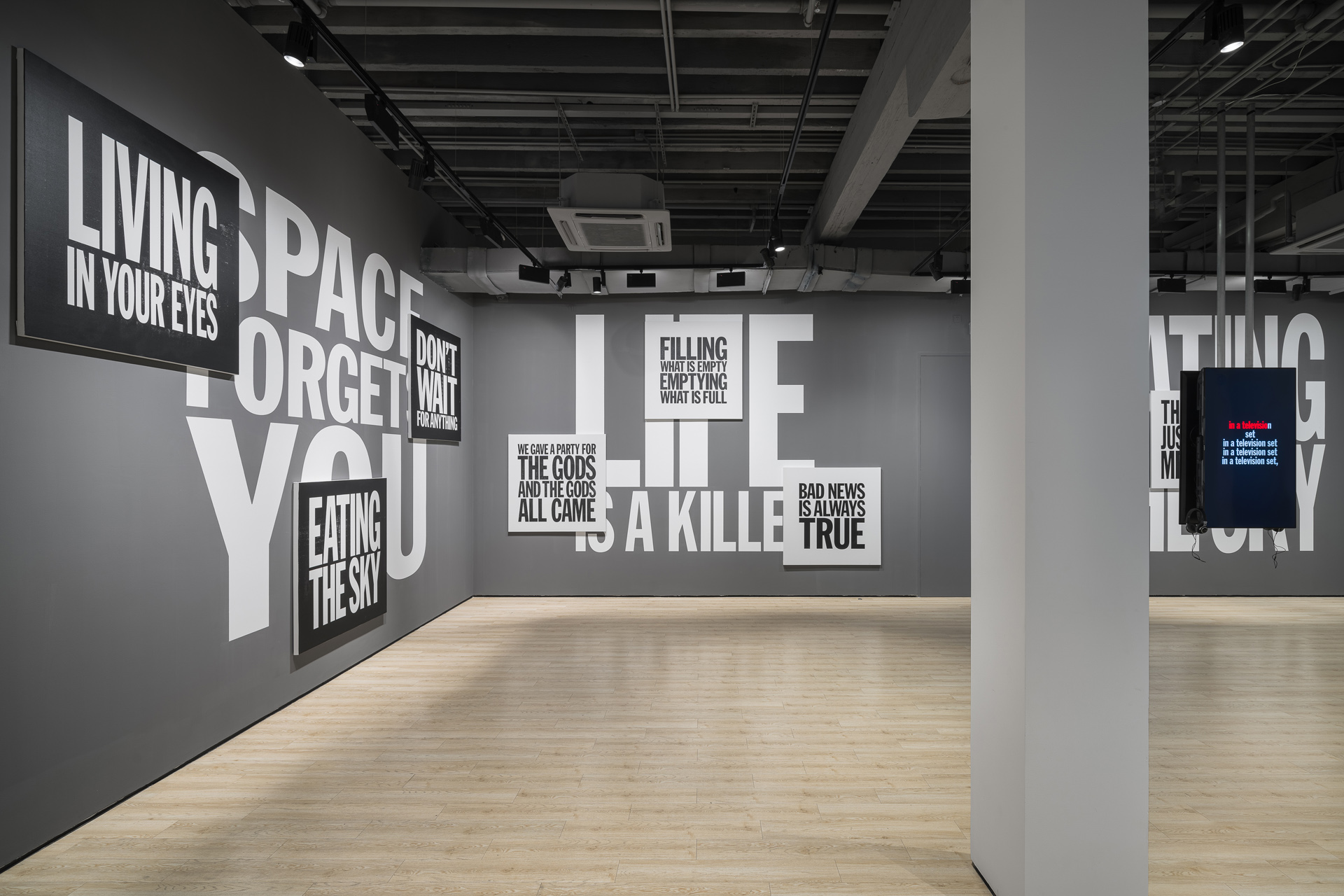

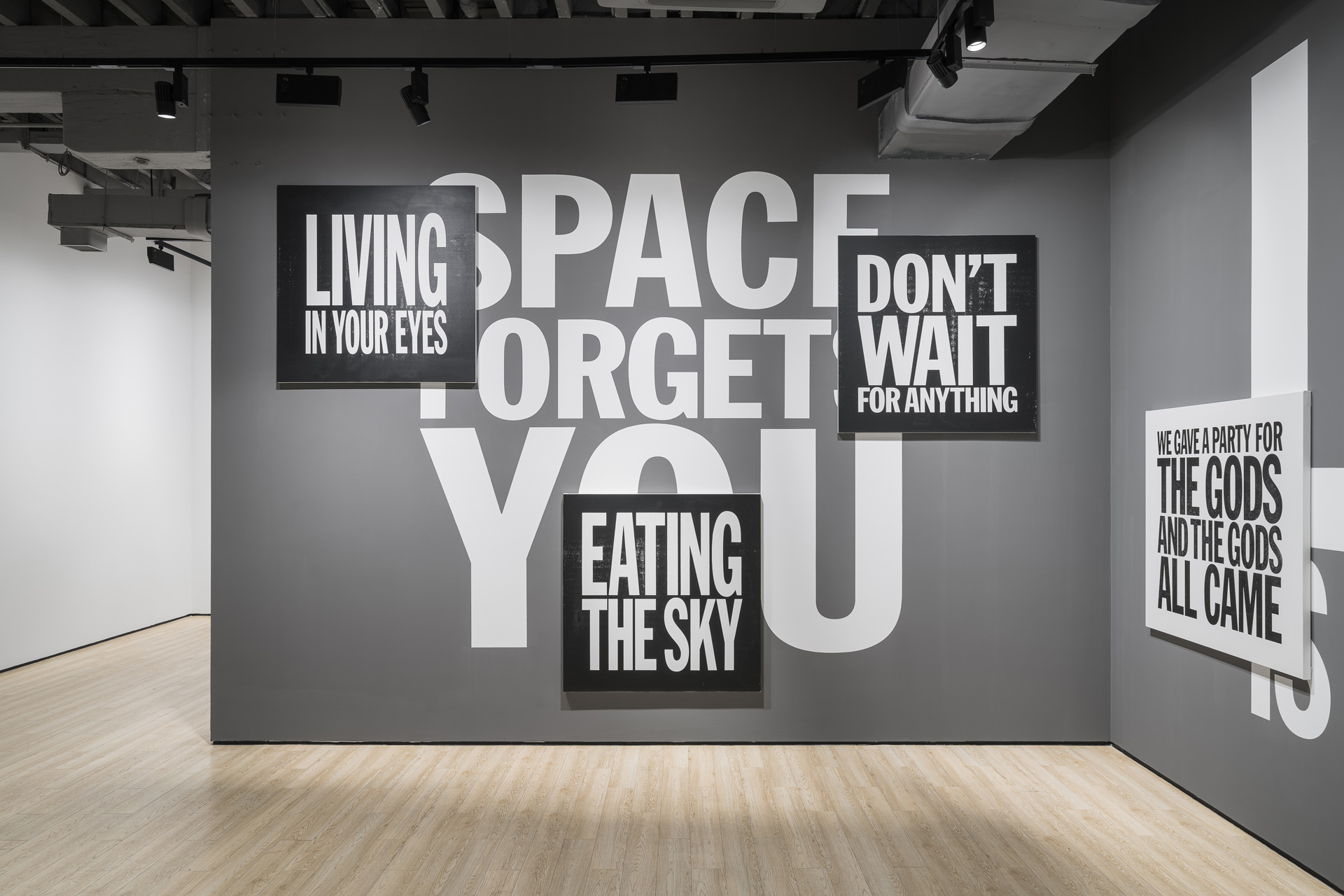

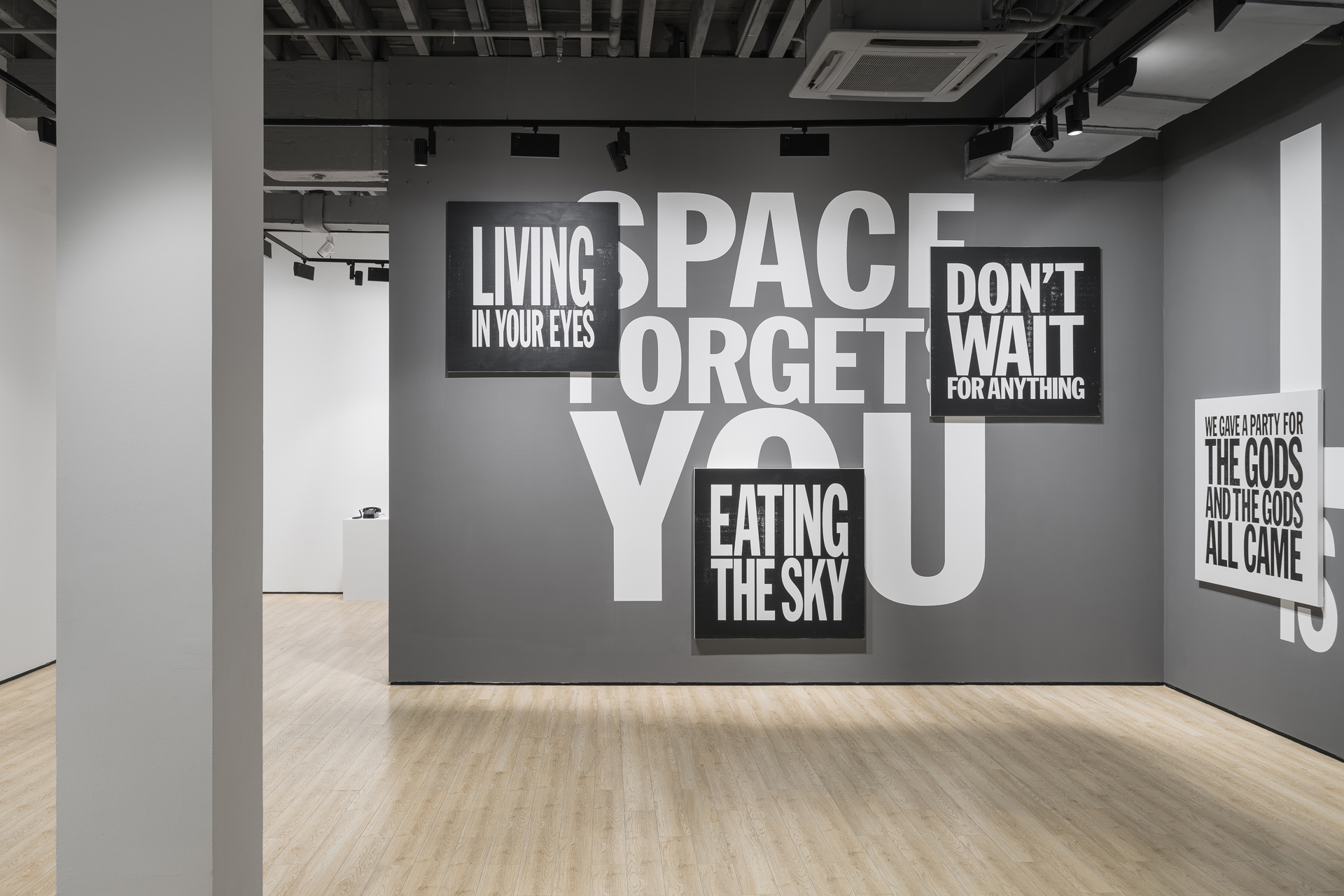

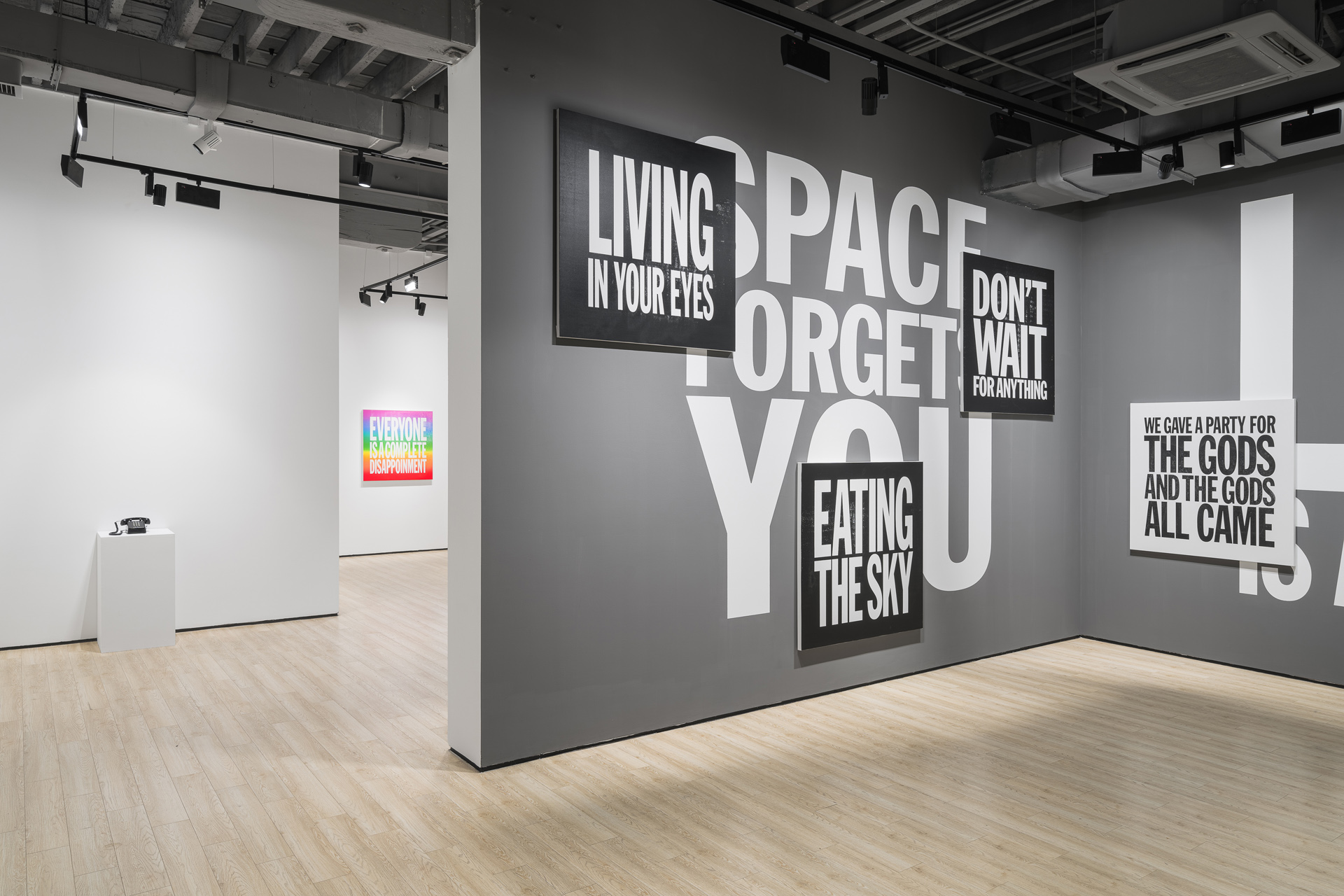

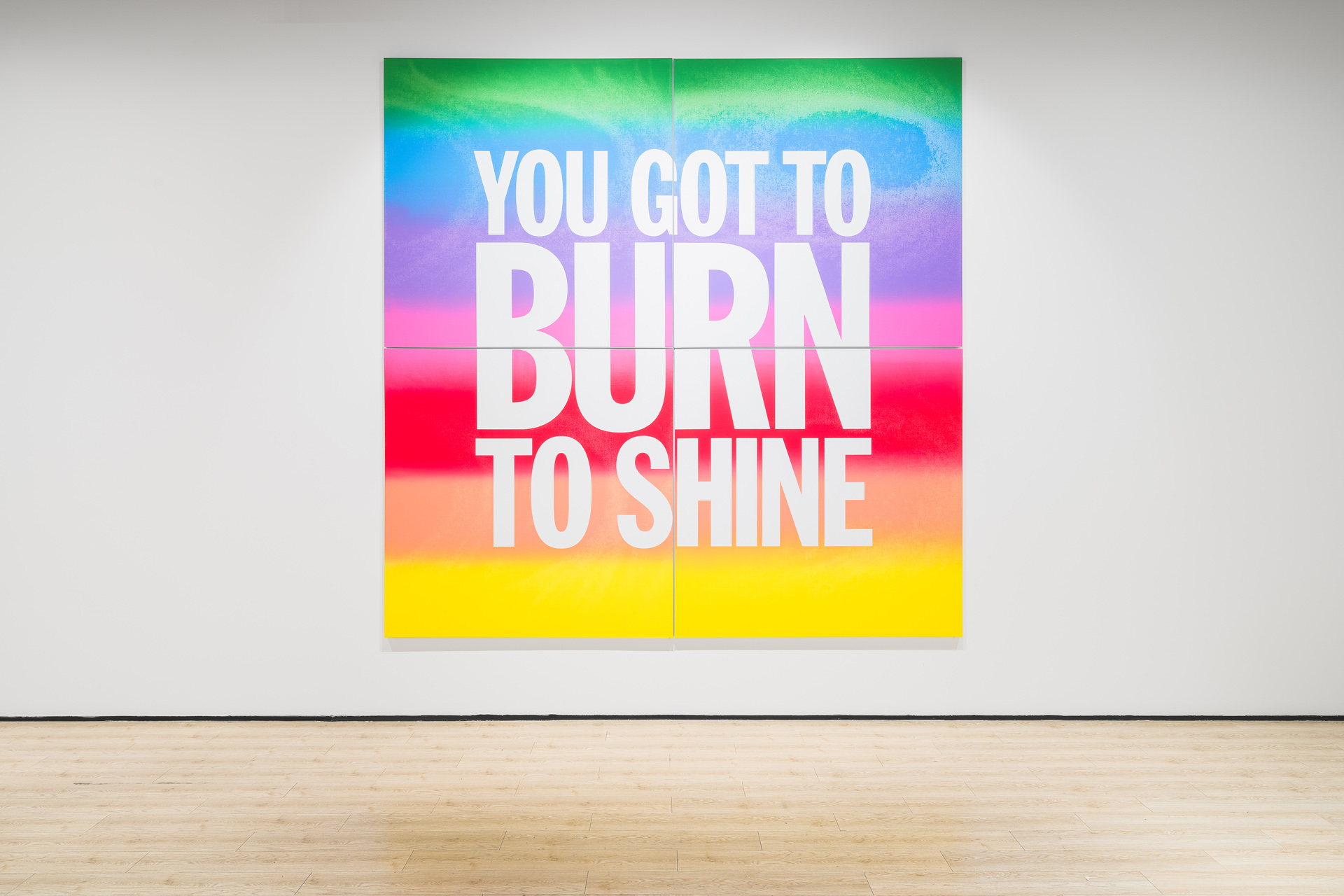

It seems that Giorno’s life and work is all about sharing the treasures he found with as many people as possible without differentiation. Just as the concept of 'Dāna' is at the heart of Buddhism, which includes the cherishing of the Three Jewels and unconditional love for others. This is the most fascinating link that connects Buddhism and Giorno's work. As early as the mid-1960s, he set off to work on the broader dissemination of poetry through the renewal of this genre. Giorno printed stanzas from poetry in a newspaper headline style on flyers, T-shirts, and other everyday objects. In the late 1980s, the artist began experimenting with screen printing on canvas, as we see today on the gallery walls. The idea of democratizing the distribution of poetry pinnacled in the work "Dial a Poem." Poetry is a form of artistic expression with a shade of elitism, and the artist uses daily action to subtly connect it with everyone. At the same time, the artist has inadvertently created a kind of "blind box" marketing strategy that we now know — everyone wants to hear their favorite poem. Giorno once said of this work, "I discovered that creating a desire that is un-fulfillable is the ultimate success." Human desires is also an implicit part of this work.

From the 1950s onwards, North America began to receive influence from Buddhist preachers led by D.T. Suzuki, Chögyam Trungpa, among others. Some of the most prominent artists, poets, and scholars of the era, including Giorno, integrated Buddhism into their vision in one way or another. However, besides Giorno, very few lived their entire lives in a way almost as 'Upāsaka' — the follower of the Buddha. The artist's bond with Buddhism began to germinate during his undergraduate years at Columbia University, and he did not limit his interest in this religion to an inner conversation or spiritual solace within himself.

In 1975, Giorno visited India for the fifth time. It was during this trip that he managed to invite his guru, Dudjom Rinpoche, to visit the United States. Giorno raised funds to help Rinpoche establish the Yeshe Dorje temple in Greenwich Village, New York City, which was eventually founded in 1976. Giorno devoted all his energy and time to this temple in the first few years. As he recalled this moment of history, he said: "I had accomplished everything I wanted to do.” In 1982, Giorno transformed his house into a Tantric meditation hall, and used it to hold a grand and solemn Fire Puja every New Year's Day for more than 30 years before his death.

It seems that Giorno’s life and work is all about sharing the treasures he found with as many people as possible without differentiation. Just as the concept of 'Dāna' is at the heart of Buddhism, which includes the cherishing of the Three Jewels and unconditional love for others. This is the most fascinating link that connects Buddhism and Giorno's work. As early as the mid-1960s, he set off to work on the broader dissemination of poetry through the renewal of this genre. Giorno printed stanzas from poetry in a newspaper headline style on flyers, T-shirts, and other everyday objects. In the late 1980s, the artist began experimenting with screen printing on canvas, as we see today on the gallery walls. The idea of democratizing the distribution of poetry pinnacled in the work "Dial a Poem." Poetry is a form of artistic expression with a shade of elitism, and the artist uses daily action to subtly connect it with everyone. At the same time, the artist has inadvertently created a kind of "blind box" marketing strategy that we now know — everyone wants to hear their favorite poem. Giorno once said of this work, "I discovered that creating a desire that is un-fulfillable is the ultimate success." Human desires is also an implicit part of this work.

The genre of poetry, which has a long history in both East and West, undergoes complex and fascinating transformations in the artist's writing, utterance, body, and visual artworks. In general, Giorno's text-based content is complex in its origins, coming from pop culture, colloquialisms, advertisements, and even Buddhist stories. Among them, I think the most relatable one to the Chinese audience is the phrase "Prefer crying in a limo to laughing on a bus," which has a striking structural and content similitude with the phrase "Prefer crying in a BMW to laugh on a bike," which has been widely circulated in China since ten years ago. However, unlike the controversies that the second phrase had been subjected to, in Giorno's work, we hardly feel any judgment from the artist himself. The opposing elements of vulgarity and elegance, the masses and the elite, are all dissolved in his works. All that remains is the dialogue we have with ourselves when we read these words. In a forewords to one of Giorno's books, William Burroughs writes: "John Giorno raises questions to an almost unbearable pitch, to a scream of surprised recognition. Litanies from the underworld of the mind reverberate in your head and ventriloquize your own thoughts."

Giorno has no intention of edifying others but rather committing himself to providing an opportunity to new experiences for all without distinction. Giorno made poetry just a phone call away, and the many Tibetan Buddhist institutions he has supported are still flourishing on the Manhattan Island today.

— Neil Zhang, curator and researcher in Buddhism

Click here for more information.

Giorno has no intention of edifying others but rather committing himself to providing an opportunity to new experiences for all without distinction. Giorno made poetry just a phone call away, and the many Tibetan Buddhist institutions he has supported are still flourishing on the Manhattan Island today.

— Neil Zhang, curator and researcher in Buddhism

Click here for more information.